How Banks Fail

Or, What's Up with Silvergate?

One of the more misunderstood topics in the world is banks. How they work, how they succeed, and how they fail are all things that are typically described with some mix of factual accuracy, factual inaccuracy, deliberate obfuscation, and straight up confusion so profound it is neither correct nor incorrect, but rather so incoherent it seems like it originated from another dimension.

To that end, in light of the current Silvergate situation, I am going to endeavor to do three things with this post:

Describe a deliberately oversimplified model of how a bank works

Describe how banks typically fail, in light of this model

Apply points one and two to the current situation at Silvergate

Hopefully, I will be able to add more detail at each step to provide some clarity. I promise we won’t do much math, either.

How Do Banks Work?

I remember vividly having a conversation with a friend of mine (who will remain nameless) that went like this:

Friend: “So you work for a bank now?”

Me: “I do.”

Friend: “Can I ask you a question?”

Me: “Sure.”

Friend: “How are banks so profitable? All they do is take people’s money and just hold onto it.”

Me: “…”

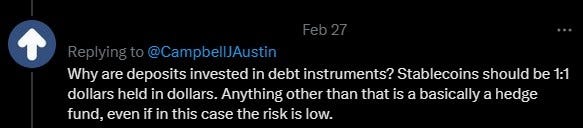

This is, shall we say, not how banks actually work. However, it’s a common misconception, and one that still shows up today:

Dollars, in our current system, are bank deposits. Which means the tweet above, which was referring to a stablecoin that was in t-bills, is arguing that it should not be in “debt” but should instead be in “dollars”. There are so many layers to how this tweet is wrong that I am going to basically have to write an entire article that also explains why Silvergate is in such a bad situation just to address it.

This is also why complex problems are awful for short form debates or Twitter: a refutation usually takes 50x as much work as the malformed question.

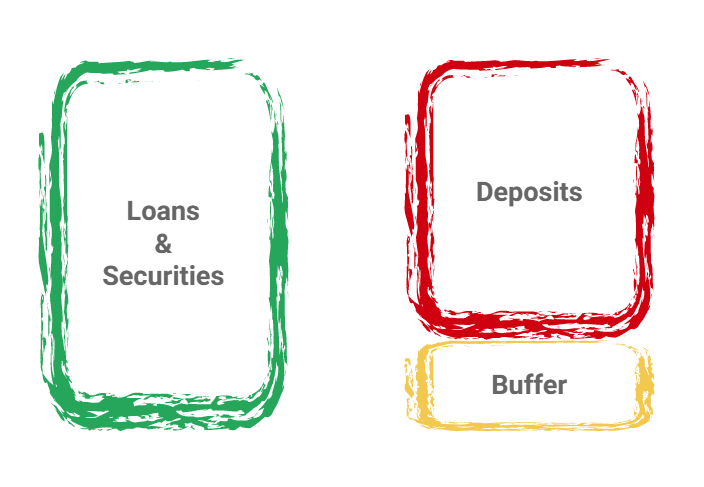

To understand why this is so backwards, let’s talk about what a bank actually looks like by starting with a balance sheet:

Simple Example Bank

This is pretty much the balance sheet of a bank, abstracted as far as possible. On one side, you have the assets of the bank, which are things like loans and debt. On the other side of the balance sheet, you have the liabilities of the bank, which are things like deposits. Then you have equity, which is the extra capital the bank uses for when it invariably fucks up and loses money.

I’m one paragraph in, and this is usually where I’m already getting confused looks or having people ask questions when I give talks, so I’m going to go through the parts that are likely to cause some brain damage for a normal mentally healthy person. If you already know this stuff, then you have my condolences, as that probably means you’ve worked for a bank. Sorry about that.

Wait you said loans are the… asset? Isn’t that money you owe someone?

Yes, that’s what I said.

Here’s the key: banks exist in the mirror universe compared to how you think about your own balance sheet.

Remember how you just said loans are money that you owe someone? That someone is literally the bank in this example. You owe them money, usually in the form of principal (the original amount of the loan) at some point in the future (or maybe parts of it at many points in the future, like with a mortgage), and you owe them interest.

If you had given someone money, and they were going to give that money back to you, plus extra money beyond just that money, so you made a profit… that’s an asset. It’s a loan or a bond, usually.

Okay, so I get that part now, at least kind of, but why are deposits liabilities? Isn’t a deposit where you put money in something and can take it back out when you want it?

Yes, that’s also what I said. Let’s go back to the banks existing in the mirror universe point. The thing that owes you the money when you come to get your deposit? Also the bank. That means if you gave the bank a dollar at a deposit, they have to be ready for you to burst into a branch, at any time1, and demand your money back. Usually politely, but sometimes impolitely and loudly.

What this means is that while the deposit is your asset, it’s a liability for the bank because at any time, they might have to give it back. It’s also a type of liability for the bank that simultaneously drives their profits (because they are ripping you off paying you a low rate of interest on them) and that regulators worry about constantly. The latter is because rather than just you, an angry mob might all show up at once to get their deposits back, which causes problems for the bank.

What kinds of problems you ask? You’re way ahead of me.

Great, now I’m not totally lost, but what about the capital thing?

Regulators, having decided that banks are pretty much incapable of not fucking up at least some of the time, don’t trust them to just take deposits and lend those deposits out. Instead, they require banks to hold a buffer, in the form of equity or other capital (again, we’ve simplified here), so that if the bank fucks up, the first people that is a problem for are the shareholders of the bank, not the depositors.

You can think of the equity capital a bank holds as a measure of the degree of how stupid a bank can be before the depositors are going to have a problem, in a lot of ways. Again, we’re oversimplifying, but if you want to understand the furious debate about appropriate bank capital ratios and leverage and why it matters that happened after 2008, this is why. It’s essentially an argument about how big of a margin of safety banks should be required to have.

Keep in mind this capital is not free, before someone in the peanut gallery shouts “obviously banks should hold all the capital ever”. More capital = higher costs. So while banks are safer, they are also more expensive for people to use. There is some effective balance here, and it’s neither zero nor infinity. Reasonable minds can debate it (and they do, constantly).

So with all that said, let us look at that balance sheet again, but now with more context, label it properly for a bank:

Now that we have more specific labels on things, we begin to see how a bank actually operates and makes money. There is an infamous old joke about the 3-6-3 rule in banking, which is that you borrow at 3%, lend at 6%, and are golfing by 3pm.

The last part is almost certainly not true (as anyone who works at a bank can attest to), but the first two are the core of a concept called Net Interest Margin (NIM), which is the difference between how much an entity pays in interest and how much the entity earns in interest. Thus, our 3-6-3 bank above has a NIM of 3%, which is quite simply2 6% interest earned minus 3% interest paid.

This is the core game of a simple bank: earn more on your loans and securities portfolio than you pay on your deposits and capital. If you can also sell a bunch of services that you charge for, even better!

This leads us to a couple of important points that I want to end this section with:

Dollars at a Bank Are Not Cash Like Dollar Bills

When you give money to a bank, that bank takes your money and does something with it. See that big green box up there labeled loans and securities? Yeah. They do that. The bank is not putting your money in a vault or a box, typically. They are keeping some amount of it on hand in case the depositors come back to redeem, but a lot more of it is being lent out.

Banks Engage in Credit Creation

In simple language, this means banks lend money to people. That seems like a trivial thing to say, but it’s important to remember the mechanics of it. Specifically, banks lend other people’s money to other people, for the most part. This is both credit creation and credit intermediation, where the bank is kind of acting on behalf of all the depositors.

Most Depositors Can Show Up and Ask for Their Money Back

While there are forms of term funding (CDs, etc.), for demand deposits, banks always have to have some degree of paranoia in the back of their mind that depositors are going to show up and ask for their money back. How likely is that? Well, that’s one of the main questions that keeps bank management up at night.

Remember those three points as we continue.

How Do Banks Fail?

Looking at the model above, I’m sure there are a number of people reading this who are thinking to themselves some variation of the following:

“This seems pretty simple. Why do banks fail, often in bunches, then?”

There are two ways a bank can ultimately fail: bad assets, or a run on liabilities. These are not necessarily independent, and that is most certainly not an exclusive or. Often they go together, but they don’t have to.

Let’s take them one at a time.

Bad Assets

Remember that picture from above? Well, let me paint you another picture of a bank balance sheet:

This is what happens when a bank loses money on its assets. At this point, the size of the “uh oh” is what matters: a small one can be absorbed by the capital that the bank holds as a buffer. You’re going to have some upset shareholders, you might look stupid in public, and the regulators are for sure going to ask some questions. But in the end, if the rest is well managed and you are still profitable, you will build back the capital and things will be fine. This was the exact experience of JP Morgan around the London Whale, for instance, while I was there. It’s not a great experience, but the bank will survive and the depositors won’t have a problem.

For a big enough “uh oh”, you probably have a problem, though. The exact threshold of big enough is not a fixed number, as it depends on when your depositors and/or regulator start getting quite upset (as opposed to merely annoyed with you in the example above), but when that happens, you are Fucked with a capital F. The only way out of this situation is to pray that nobody notices how big of a hole is in your balance sheet, that the depositors don’t demand their money back, and that you make enough money on the remaining assets to fill it back up over time.

In practice this rarely works, but it does explain why even the most beleaguered bank executive will express extreme confidence in public. The moment a bank CEO goes on Bloomberg and says “Actually, we’ve lost a shitload of money so if everyone showed up to get their deposits back, there’s literally zero chance we could pay them all”, you can bet every depositor will show up as quickly as possible to try to get their money back and then the game is over. Instead, that bank CEO, the one with the giant “uh oh” on the balance sheet, will go on Bloomberg and say everything is fine, the bank is profitable, operations are normal, and life is good and sunshine and beaches and nobody panic (while screaming on the inside).

So how do you lose money as a bank? There’s a lot of creative ways to do this, but I want to focus on two main ones here.

Bad Loans

This one is simple, and it happens a lot. You loaned money to the wrong people, and by wrong people, I mean people who are not going to pay you back the money that you loaned them. This is basically the TL;DR version of the entire subprime mortgage crisis in 2008. Loans were made to people who could not pay them back. Those people did not pay them back. A bunch of people lost money because of that, including banks. Some of those banks died.

Banks are typically going to call this default risk, so if you hear people talking about it, this is why. There are a lot of types of risk around loans and defaults, such as the very vanilla type we just mentioned where you loaned someone money and they didn’t pay you back. Another example is the somewhat more exciting counterparty credit risk, which is when you have a trading counterparty that fails to fulfill some obligation (usually posting margin on a derivative position, which is way beyond the scope of this exercise) and you have to close them out or do something else nasty, often at a loss. That was at the root of the problems with the CDS market and AIG in 2008.

In short, though, it’s simple in the end: someone owed you money, somehow, and they didn’t pay you. Fuck.

An important part of this type of failure, though, is that it’s usually a multi-level failure of risk management. Banks are supposed to lend at a profit, to a broad and diversified group of borrowers, with that diversification spanning things like time, types of borrower, creditworthiness, core business activity, and so on. In practice, that’s not so easy. But what it means is that either you seriously misjudged the ability of people to pay on large loans, you made a lot of concentrated loans that all went bad at once, or both. One small loan going bad won’t bring down a bank (remember that buffer?).

Duration

So many of the readers of this article, assuming you are enough of a masochist to have made it this far, will have heard the phrase “maturity transformation” before when discussing banks (as opposed to teenagers). What this ultimately means is that banks have a tendency to “borrow short, lend long”.

Or, in plain English: they have demand deposits, which depositors can come ask to get back at any time, and they use those deposits to make long-term loans, which the bank can’t just go ask someone to pay back merely because someone wants their deposits back.

Usually this works fine. When interest rates are stable and loans are performing, you can file this solidly under “who cares” in most situations.

However, there’s a specific case where this is often a problem, and that’s when interest rates are going up. Why is this a problem?

Loans and bonds are typically fixed rate (e.g. you pay 3% interest), and when interest rates go up, those bonds fall in value. I promised there would be no complex math, so we’re not going to get into why, other than to say in English words that the reason this is true is that if interest rates are now 4%, the price someone will buy your 3% bond at is a big enough discount such that they are essentially getting 4%.

So let us engage in a thought experiment.

Imagine a bank bought a bunch of long-dated bonds.

Imagine interest rates go up because Congress spent a shitload of money, and the Federal Reserve didn’t notice and left interest rates at zero and now there is a ton of inflation. The Fed suddenly realizes everything is fucked and massively increases interest rates over the course of a year.

The price on those long-dated bonds the bank bought go way down.

What happens to the bank?

If this isn’t a big problem and the uh-oh from this loss is less than the capital, usually they just end up getting some unfriendly phone calls from their regulator and have to chill out for a bit until they recover by earning more interest. Shareholders tend to hate this because they will have to stop paying dividends or engaging in buybacks until the capital recovers. Overall, though, this is a mild problem.

A slightly more major problem is if depositors notice and get restive, as once they come in and want their money back, you either need to be able to borrow against those securities so you aren’t a forced seller, or you are a forced seller. This is quickly bleeding into how banks die from deposit runs, and these issues are intertwined, but just know that borrow short, lend long is specifically a problem in the case where you did the lend long part into rising interest rates or credit spreads (which do the same thing as interest rates, but only for credit risky bonds, so not treasuries).

Volatile Liabilities

Let’s create a theoretical depositor for a bank. We’re going to call this depositor Omid, which is totally a coincidence and not me teasing one of my friends by naming the worst depositor ever to live in a hypothetical example after him3.

So this Omid guy? He’s awful, if you’re a bank. Why? Because his deposit behavior makes no sense, and worse, other people listen to him. What do I mean by this? One day, Omid shows up. He’s got millions of dollars, and deposits them at your bank. Congrats! That’s a bunch of funding. Sometimes, you will think you are even more lucky when a bunch of Omid’s friends show up and deposit millions of dollars as well. Look at all these deposits! Better make some loans or buy some bonds.

Everything seems great, except about four months later, Omid comes back and he wants his deposits back. Why? He doesn’t need a reason! So do his friends. All at once. And now, you have a problem: you have millions upon millions upon millions of dollars that you need to raise to pay all of these people, but you went and bought loans and bonds.

Now you have to sell them.

In normal times, where they haven’t changed much in price, this is annoying. You might end up paying bid/offer to unload some things, you might not be at the same investment targets you thought you were at, and you might have to borrow some money to pay people out and then sort things out later. Specifically, you might have to borrow money using Fed or FHLB facilities, which can be a signal to the market that you have a problem, all because this one dude started a trend of people leaving your bank. Annoying!

However, in times where those loans and bonds have lost money, you have a problem. Not the small kind of problem that will go away, but the big kind of problem that is about to kick your ass. Why? Because you are selling at a loss. If you bought $10mm of bonds that are now worth $9mm, and people come to demand $10mm of deposits back, you’re out the entire set of bonds and you need to go find another $1mm somewhere.

This is why hot deposits are a problem. Unless a bank knows in advance that those deposits are hot money, if they go and buy long-dated securities or make loans against them, it’s going to be a problem when they redeem.

Another factor about volatile deposits is that usually, the depositor is not irrational like Omid, but actually is quite unfortunately rational. Why do they want their deposits back? They probably need the money to pay for things because their industry is in trouble. Which is the same reason all the other correlated deposits are redeeming as well. This is what regulators mean when they talk about hot money and runs on the bank being caused by certain industries.

A Live Example

This all brings us to Silvergate.

For those who don’t know, Silvergate was one of the banks that was an early supporter of the crypto industry. And by supporter, I mean merely a bank that did not aggressively turn away crypto clients and was instead willing to at least consider working with them.

Considering that most of the banking industry has reacted to crypto about the same way someone would react to a person running up and shitting on their porch, this was actually quite remarkable and forward-thinking on the part of Silvergate.

Silvergate also ran something quite notable called SEN, which is important to understand insofar as it was both the main reason for all the deposits and it was just shut down this Friday, March 3, 2023.

SEN is an instant payments network. Keep in mind that normal banks are only open during weekdays, during banking hours, and use fedwire (mainly, there are other forms) to send money. That means if you want to send money and have it settle with finality at 2pm on Saturday, here’s what you do:

Wait until Monday morning.

First of all, let me say this is positively neolithic at this point. South Korea, for example, has had a real-time payments infrastructure in place since the early 2000s. For those who object to me using South Korea because they are both small and a technocratic dictatorship, some other countries that have fully deployed, fully functional 24/7 real time payments include such micronations as Brazil and India. Put differently: the US has no excuse here and this is one more example of America not being a serious country anymore.

Second of all, what this means is that if you are crypto company, weekends become death. Why? Your primary market is 24/7, that being crypto, but if you want to trade, you…

Wait until Monday?

That’s not going to work in many cases. Instead, everyone banked at Silvergate because of SEN. What that meant was that if I was at firm A, and wanted to trade with market maker B, we could trade at 2pm on Saturday and as long as the money was at Silvergate, Silvergate would move it in real time from firm A’s account to market maker B’s account at 2pm on Saturday, instead of waiting until Monday morning to open.

For those of you being like “so, seriously, the innovation here was being aware of time existing?”, my answer to you is yeah, basically that. But Silvergate did a decent job with the implementation (as did Signature, another big crypto bank, with Signet), so people used it. In size.

You’ll notice I said something interesting just above there: “as long as the money was at Silvergate”. Now let’s take that little tidbit and put it back in the language we have been using to talk about banks.

This means a customer has deposits at Silvergate, and those deposits can be used 24/7 on SEN to pay other customers of Silvergate. This creates quite the little network effect, which served as an excellent asset gathering tool for Silvergate. Silvergate’s economic terms were also terrible (0% interest, and even charged people fees to use SEN), so they were making absolute bank on these deposits4 so long as they could deploy them at any positive interest rate.

So what happened with Silvergate? Here is the timeline, as best I can reconstruct it:

Silvergate, with SEN, had the pole position in crypto and a deposit base that was mostly crypto companies heading into 2022.

Riding high on these deposits, Silvergate decided to buy longer-dated assets, which look to be some mix of treasury bonds, agency debt, and agency mortgages, exactly the kind of thing you’d expect a normal bank with a boring deposit base to have.

In 2022, as Terra/Luna happened, Silvergate largely appeared to be fine, but then after the FTX crash, finally began to experience large drawdowns in their deposit base. They allegedly lost approximately 70% of their crypto-related deposits in the fourth quarter of 2022, which is a lot!

This, back to our examples above, forced Silvergate to begin selling securities that had declined in value thanks to J.Pow & crew going fucking hard at inflation and raising rates multiple percentage points over the course of the year.

Silvergate had been stumbling around drunk and wounded for several months after that, having lost at least $700mm on the sale of securities to pay out the departing depositors.

However, this past week, they were cut off by the FHLB, appear to not be able to make a filing deadline with the SEC due to some kind of accounting or balance sheet issue, and shut SEN down after the close of fedwire on Friday.

This is the kind of thing that happens when your bank is about to die. In this case, the path is pretty simple, and it’s one of the things that was discussed above as a basic reason banks die: borrow short, lend long, lose money on duration, and then have your depositors ask for their money back.

The only part of this tale that is shocking to me is that they did it. Silvergate is the ideal bank to do nothing other than own t-bills and just rake in profits, given they were paying 0% on deposits. In that world, why take the duration risk? I’m genuinely curious as to what the thought process was behind the securities they bought. Hell, even better would be ON reverse repo with one of the big dealers or custodians, and that was paying even more than t-bills for most of the year!

There were plenty of highly profitable debt trades that would not have created a material mismatch in duration, but that doesn’t appear to be what they went with.

So what happens now? It’s unlikely that Silvergate can recover from this, in my eyes. It’s likely that someone buys them at a highly distressed price or that the FDIC puts them into receivership (which is roughly the same thing, now). Either way, you don’t create this degree of crisis of confidence and bounce back.

In terms of lessons for other banks in the space, I would suggest everyone should note the following:

If you don’t have a highly diversified asset base where crypto is a small part of your lending, be careful on the asset side here. I won’t say more because this is literally something I advise banks on5, but suffice to say it’s solvable.

In a rising interest rate environment, be very careful about extending out in duration in general, even for non-crypto exposures.

Don’t act like a jerk to your customers because they won’t cut you slack when things go wrong.

Full Circle

Now let’s come back to that tweet above. Remember the person who said stablecoins should be in “dollars”, which in our system are bank deposits?

When a bank fails, you might lose those deposits. In this case, Silvergate is plausibly going down, and given the FDIC6 will only cover up to $250k, I’m pretty sure that’s not going to help the major stablecoin issuers.

As a general statement, if Silvergate goes through receivership and the depositors are made whole, things could work out okay. But if they fail in less orderly fashion, or there’s not great bids in receivership, depositors could take a big ding.

In general, bank deposits work this way: you are reliant upon the risk management and credit underwriting of the bank you are depositing your money within order to get it back. Put differently: banks are credit risky!

The punch line for that tweet above is that a stablecoin invested entirely in t-bills would be fine right now, but one that had left money at Silvergate might be about to lose a bunch of money if things get worse.

“Dollars” were not the safe bet.

And by at any time, we usually mean during normal banking hours, 9-5pm, on weekdays that are not bank holidays.

Another dark truth of finance is that the more jargon and acronyms are being used, the less complicated the actual business, as a general rule.

Omid and I worked together at Citi, and I actually think the world of him. He’s a genuine expert and intellectually honest, which is a rare thing in this world. He is also awful at self-promotion relative to his level of talent, so I may have done this so more people know his name and buy his new book, which I highly recommend.

This bare-knuckled approach to economic terms, however, may have bitten them in the ass when it came to the crisis moment, as more than one person in the market I spoke with shed zero tears for Silvergate and were more than happy to cut deposits once they started looking shaky given how they had been treated over the years. A lesson, perhaps, in the old-school Goldman Sachs vein of being long-term greedy instead of short-term greedy.

I don’t typically give financial advice, but I’m going to give a very limited form of it here against my better judgment: bank deposits are insured by the FDIC, on a per-person basis (not per account!), up to $250k at a bank covered by FDIC insurance. Never more than that for an individual. If you have 3 accounts with a total value of $100k you are going to get your money back, assuming the FDIC is solvent, but if you have 3 accounts with $300k, you have $50k at risk. Likewise, this is only easy to understand if you know there are no other institutions with money at that bank in your name (such as those using FDIC sweep products, etc.), and only if the money is in your name. Thus, as a general rule, be VERY skeptical of anyone in the crypto space claiming FDIC coverage. I barely believe it when my own bank tells me I have it, and I worked for several banks. More so, if someone says money is at “FDIC-insured” banks, that’s code for “LOL UR FUCKED” if a bankruptcy happens. You, specifically, the two-legged human, need FDIC coverage. Not the bank.

It’s nearly three years since you wrote this but just found this and it caught my attention … Great first substack post but did you, perhaps, miss the biggest point of all about banks?

This is a useful article for anyone new to the banking world to explain essentially how Fractional Reserve Banking works (Omid deposits millions, the bank then lends out the majority / a big fraction of that money and only keeps a small fraction as the regulatory required buffer in case of demand / threatened bank run) and hints at a kind of rehypothecation (Omid’s money that was now lent out finds itself back as deposits at other banks and is similarly re-lent out by other banks so only a tiny fraction of his original money is held by the collective banks - when you put Omid and everyone else together FDIC insurance doesn’t remotely protect anyone, but that doesn’t matter since depositing it the money no longer contractually belonged to Omid anyway).

But the point now for this comment is to raise the bigger misunderstanding of banking and credit creation. Our great schools of Economic learning teach banking as you’ve described it, but the actual reality is different again. We are taught modern money is only created centrally as sovereign currency notes and coins, with money printing supply only increasing inline with GDP growth otherwise currencies devalue and inflation runs rampant.

Wrong! Commercial banks actually create the vast majority of modern money ‘out of thin air’ through the process of new lending. They create loans as assets (think of your balance sheet picture) and by a sleight of hand, and as if by magic, they create matching ‘deposits’ on the liabilities side. No depositors involved, no actual ‘currency’ money needed. These are not like deposits as you describe them, but help the books appear to balance and seem legitimate.

All of this new credit / ‘deposit’ money creation is then magnified by fractional lending as you describe, scattered out into the banking and non-banking markets to be re-lent though weird and wonderful financial vehicles, perpetuating wealth in the financial system.

And it’s a big deal - Omid and other depositors (our granny’s savings) only account for about 3% of deposits in the banking system whereas bank-created / electronic ledger deposits make up a whopping 97% of the western money supply. This magic money creation is a trick that’s unique to commercial banks by virtue of their Banking Charters (in the US). Here in the UK we call it a ‘banking licence’ - literally ‘a licence to print’ money!

Currency - what we think of as real money - is only the 3%, the rest of (digital) money in the supply is bank created.

Not all banks do this and in fairness to your article - at the time about Silvergate - I suspect Silvergate were not part of the money-creation club.

I’m guessing you’re aware of this but it might be worth coming back to in your current work because it changes the lens on all things Macro from M2 money supply, to FED policy behaviours, to exploding sovereign debt, to the rise of NBFIs, to falling GDP, to further polarising wealth inequality and opportunity.

It also explains why nearly everyone misunderstands QE / QT (QE worked in 2010 by feeding bank buffers to re-start out-of-thin-air money creation and bank lending), and the limited influence and mechanics of central banks as the real economic power is held by commercial banks, not western governments or regulators, not even ‘the markets’.

This magic money creation has been going on at pace for over 50 years, prior to the era of modern computerised bank systems, and started in 1971 with Nixon ditching Bretton Woods / the far older standard of backing of money 1:1 with gold. But for the last 15 years this modern money creation has been on steroids.

Many commentators correctly get so much about economics correct but miss the fundamental source of money creation and supply. This is no accident - banks, and particularly central banks, work hard to keep their biggest trick a secret, including from most of their own banking colleagues (particularly boards and execs in my experience). For instance, central bank QE is small change by comparison to commercial bank money creation, but too many commentators have been cleverly mis-directed to call QE the ‘money printer’ or blame it for the increased M2 money supply.

But on a sobering note this is also the reason to worry most because markets are currently obsessed with credit renewal and it matters to banks - not only for their greedy profits but now simply to existentially survive - as money supply (all kinds of bank and NBFI debt) are gradually spiralling out of control. It’s like understanding the magic trick but watching in slow motion how the magicians are setting themselves and the whole theatre on fire …

Gold and bitcoin may offer an alternative, but they’ll be little antidote for the economic and societal Armageddon following any collapse of the institutions underpinning sovereign money.

What happens to the shareholders at silvergate, are they done for